By: Heather Bushman

Let’s talk about labels. We have them, we use them, and, frankly, we’re obsessed with them. We, as humans, like facts and figures that point to one right answer, quelling our questions with a simple solution and tying everything up with a neat little bow. The evidence of this phenomenon is everywhere, but its presence is especially strong in music as the art of genre.

There’s a change on the horizon, though. Society is slowly shedding its label-intensive outlook, and music is following suit. We aren’t so preoccupied with giving people a label anymore, content to just appreciate intrinsic qualities over external titles. Based on the records that have made waves and the listening patterns within the community, it looks like music is headed in that same direction. Genre, more specifically the pressure to stay put within it, is fading away.

It’s naive to assume that genre exists without reason. Much like labels, genre is beneficial from an organizational and preferential standpoint. Placing compositions into categories like “rap” or “rock” makes access and analysis of music much simpler than if all music were just thrown together as a general idea. Music is evidently much more complex than that, and genre assists a guide to sorting through this diversity and deciding what works for you. Identifying the common thread in these selections makes it easy to continue building your personal library, giving it a name even easier: After all, to find something, it’s best to know what it is you’re looking for in the first place. Discovering your likes and dislikes is how you develop your taste, how you forge ahead in your listening habits and amass an entire collection suited to what you enjoy.

Traditionally, genre has been on the side of artists as well. From the introduction of Top 40 in the 1970s to the pre-stream early 2000s, the era where radio play was the deciding factor in artist popularity, genre was the all-important entity. The absence of streaming is especially significant here; it means that it was impossible, save for radio, to consume music without making a monetary commitment. The only way to “test” a song was to hear it on the radio, and in order to make the radio, the song had to fit the mold of what was popular at the time. Enter genre, the very definition of a musical mold. Subscribing to it was how an artist found success back in the day: picking a lane and sticking to it, then hopefully earning some airtime, a spot on the charts, and decent record sales. There’s a reason we didn’t see top-selling artists like Michael Jackson, The Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, Whitney Houston, and Madonna, among many others, really deviate from their core identity as musicians: They found a musical niche and maintained a dominant presence within it, fine-tuning their brand to consistently deliver content that satisfied commercial expectations.

Looking at music production and distribution within the context of human behavior, it’s not hard to see why genre, or at least a steady set of musical bounds for an individual artist to stay strictly inside, persists. Whether we’re conscious of our attachment to these expectations or not, we are reassured by reliability. That’s not to say that we don’t appreciate variety or innovation (just look at the reverence The Beatles receive for their later experimental years), but consistency is key. Humans prefer to know what they’re getting into in the day, or the music, ahead, and the easiest way to familiarize a concept within the collective consciousness is to give it a label. The phenomenon can best be attributed to Aristotle’s idea of form. When we picture a chair, let’s say, we produce a prototype image based on an amalgamation of all of the chairs we’ve encountered in our life rather than one specific chair. The same can be said for music, and that’s where genre comes into play. When we picture “pop music,” we don’t mentally generate one specific song, but rather a concept based on the combination of all of the Katys and Justins and Mariahs with whom we’ve become so familiar.

But there’s a downside. As with the idea of labels in general, the preoccupation with adhering to a genre can severely inhibit the ability of a creative to simply create (I won’t even admit how long l struggled with what to call this piece before I wrote a single word of it). We rely on cut-and-dry, so much so that we lose sight of the beauty in art just existing. In all likelihood, the confines of genre and artist expectations have prevented some seriously incredible compositions and collaborations from coming to fruition. What would an Aretha Franklin track look like with a guitar solo from Jimi Hendrix, or Carole King-penned power ballad for Van Halen? How about a Britney record with assists from Wu-Tang, or Usher on a Sugar Ray single? Cross-genre compositions like this did happen, sort of, but for the better part of music history, artists have stayed in their lanes. Yes, music that kept the course is incredible in its own right, but there exists a sense of curiosity for the projects that could have existed had artists been relieved of this commercial burden.

Back to that good news, though: we’re headed in the right direction. It shouldn’t come as a shock that streaming services, and the internet in general, are the prominent catalysts from a listening standpoint. With music so accessible, we’re able to taste-test without a monetary commitment and without relying on radio. In a fascinating article examining our relationship with music from problematic artists, Pitchfork contributor Jayson Greene put it best: we don’t “own” music anymore, we simply rent it and send it back to the original database when we’re finished. Record sales still exist and still matter, of course, but the majority of music consumption occurs through the internet without a direct purchase.

It’s also worth mentioning that streaming services possess virtually no barriers to entry for an artist. Making the radio is a huge testament to a song’s popularity, but anyone can throw a song on a service in minutes. There’s no guarantee that the song will gain any traction, but it exists and is available for consumption in a commercial space. That alone eliminates the radio popularity hurdle: a song doesn’t have to fit a mold or subscribe to current trends or even be good to have a presence in a music library.

The idea of genre-crossing is especially notable in personal playlists, where the listener has complete control in its creation. Maybe the idea of weaving in and out of genre really is a reflection of our shrinking dependency on a label, or maybe we’ve always been open to it but too comfortable on cruise control to notice, but either way, our preferences aren’t confined to a single genre. The playlist I have on right now puts Grimes and Rico Nasty back-to-back, then throws in a Mac Miller and a few picks from the boygenius EP. Random? Sure. Realistic? Absolutely.

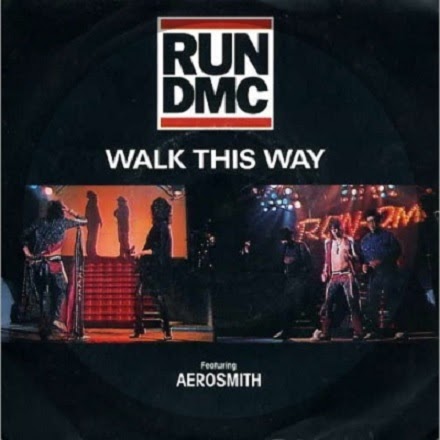

Remember that crazy idea about Wu-Tang on a Britney song? Turns out, it’s not so crazy after all, and we see it put into practice almost everywhere. No, you didn’t miss a Ghostface Killah verse in the middle of “Oops!…I Did It Again,” but that concept of a genre-crossing from artists is incredibly present in modern music. It makes an appearance most often in the form of a collaboration. The idea was first seen, and still most prominent, in the rap/pop fusion, with rappers lending a few bars to a standard Top 40 track or pop stars cranking out catchy choruses to a rap hit. The legendary Run D.M.C./Aerosmith “Walk This Way” remix introduced the fusion, 90s icons like Tupac and Biggie propelled it forward with pop choruses on hits like “California Love” and “Juicy,” Kanye perfected it with the pitched-up samples from the likes of Marvin Gaye and Chaka Khan on 2004’s The College Dropout, and now we get to laugh at the pure predictability of Ed Sheeran hooking an Eminem song or yet another feature from Quavo.

It’s not a stretch to say that the elements each has borrowed from the other have been integrated into both; Rap features are now staples in pop music, and catchy pop choruses find their way onto rap tracks time and time again. The lines are effectively blurred, and though the differences between rap and pop are clear and present, the overlapping elements can make it hard to tell where one ends and the other begins.

If rap and pop was an absurdity just thirty years ago, I can’t help but wonder how listeners back then would receive some of the collaborations and genre crosses we see today. Artists aren’t just knocking next-door for a helping hand, they’re reaching entirely across the aisle and interweaving elements that, according to the rigid genre structure, absolutely should not work in conjunction. But they do. R&B great Ms. Lauryn Hill introduced the idea of radical crosses in pulling from genres one thought possible on R&B compositions, riffing on everyone from Frankie Valli to The Doors on the groundbreaking 1998 record The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill. After the album proved to be a smash, taking five wins including Album of the Year at the 41st Grammy Awards, music production started to drift further outside the designated categories in hopes of replicating the same success. Today, we see that the strategy worked, and it seems that the more extreme crosses are finding better public reception. Florida-Georgia Line, a group you literally Can’t Say Ain’t Country, sports a feature from Nelly on the 2013 hit “Cruise.” I’m not sure it’s quite the interpretation of Country Grammar that anyone, even Nelly himself, envisioned, but peaking at #9 on the Billboard Hot 100, “Cruise” further proved that extreme genre crosses could garner significant chart success.

With these cross-genre compositions stretching further and further across the spectrum, it feels like the possibilities are endless; in truth, they probably are. In the past few years, we’ve seen the industry become more connected, more creative, more fluid, and we’re getting more interesting music because of it. It’s a shame that songwriting icons like James Taylor never turned one out for The Clash or ZZ Top, but Ezra Koening (Vampire Weekend) racking up a few songwriting credits on Beyonce’s Lemonade comes pretty close. We’ll never know what Diana Ross’s take on a Hall and Oats slow jam would sound like, but Rihanna gave us her own interpretation of Tame Impala’s “New Person, Same Old Mistakes” on 2016’s Anti. No, Jimi Hendrix never shredded an Aretha ballad, but we did get John Mayer grooving his way through “White” off of Frank Ocean’s debut album, Channel Orange. It’s records and compositions like those from Frank Ocean, the surf-rock inspired guitars mixed with trap percussion and smooth R&B keys all under some eclectic vocoder harmonies, that feel like manifestation of this merge: pulling from a number of different genres to produce a unique sound and, subsequently, some of the best albums in recent memory.

Genre exists today not as a trap but as a toolbox, each one offering distinctive elements for artists to mix and mold. We’re seeing them do exactly that, drawing inspiration from the hallmarks of multiple genres to create sonic landscapes that transcend definition. The way Kacey Musgrave’s Golden Hour layers country characteristics over typical pop production is a revelation, lush and romantic and simply magical. Taylor Swift released what’s still regarded as her best record to date, Red, with a similar mindset, meeting in the middle of upbeat pop and earnest country and using the best of both. Ariana Grande’s thank u, next still represents her pop-driven musical persona, but some elements, especially in percussion and rhythmic structure, feel decidedly hip-hop. In the grand scheme, artists probably do express a dominant genre. Kacey Musgraves is, by most accounts, a country singer, and Ariana Grande is the closest thing this generation has to a full-fledged popstar, but that’s not where the conversation lies anymore. Though genre preferences are somewhat apparent in these artists, the point is that no one is asking them to articulate those. Instead, we appreciate the additional elements from other genres and regard them as record-enhancers rather than diminishers. Our lack of concern for exactly what genre to which an artist belongs is apparent in the genre-crossing works that they’re able to produce, now without fear of industry scrutiny.

Musicians, unrestrained by genre pressures, aided by the collaborative efforts of their peers, and unquestioningly supported by a loyal fanbase, are gaining the confidence to try new sounds and styles, and it’s paying off. After Laughter, Paramore’s full departure from a hard rock core to a softer synth-pop structure, was an instant favorite despite the absence of the signature sound that drew fans in the first place. The success is largely due to the devoted following that the band has gained over their decade-and-a-half stretch, down for whatever authentically reflected their artistic vision and putting full faith in Paramore’s musical instincts. It also helps that After Laughter as a standalone piece, removed from the context of Paramore’s musical and commercial prominence, is a great record. That’s what we care about now, great records, and not the genre context of who should or shouldn’t be making them. Taylor Swift was country’s next superstar, but cut to ten years later, and she has an Album of the Year win under her belt for the pop powerhouse that is 1989. She arguably set the standard for making drastic musical shifts like this, and what we see now are many artists unafraid to take their music in a different direction.

I like to think that our culture officially abandoned the genre-centric outlook with our enthusiastic acceptance of one of the most eccentric works in music to date. Tyler, The Creator is, for all intents and purposes, a rapper, but his 2019 release IGOR is essentially genre-less. Yet, it’s still his most popular and acclaimed release. SoFlo’s own Thomas Holton touched on this in his article on the prospective projection of trap music: IGOR is not a rap album, it’s a shining musical moment. The fact that the Grammys categorized it as such despite the fact that Tyler only raps on about 25% of it (and that’s being generous) is more a reflection on the deeply detrimental genre-centric outlook of industry executives than on the cultural consciousness. The closest you could come to categorizing it would be at the intersection of neo-soul, hip-hop, and electronic, but at the end of the day, it doesn’t matter what it is: fans and critics alike devoured a record that was as fresh, exciting, and innovative, not caring that they didn’t know exactly what to call it.

In truth, we still like our labels. We still want our t’s crossed and our i’s dotted, still prefer our loose ends tied and our questions answered, but the difference is that, today, we don’t demand it. We’re not asking each other to constantly define ourselves, and honestly, we’re better off for it. Labels and titles do not matter, and maybe they never did, but now we have the agency and the independence to create a culture, and a music industry, that reflects that sentiment. A song doesn’t have to be radio-ready to generate some steam, an artist doesn’t have to stick to a single set of expectations to maintain a steady fanbase and commercial success, and listeners don’t have to limit themselves to one genre in their listening experiences. What matters now is, simply, good music, and we’re now in an age where all of the tools to compose said good music are instantly accessible. The components of genre and type that used to limit artists are now at their full disposal, allowing them to pick and choose elements across the spectrum that best suit their artistic aspirations. We’ve already seen what happens when musicians make those moves, and it’s only going to get more inventive and inspired from here. Music is a culture and a craft that thrives on collaboration, and when we rip the labels off and reach out, there’s no telling how connected and creative we can get.

Soflosound.com is your one stop shop for a hip hop fan’s music reviews, profiles, and essays. By the youth, for the youth, and allied with all oldheads, everywhere. Leave a comment below on what you want to see next!