By: Thomas Holton

Trap music is the default.

It grew up alongside me. It was invented before I was, by TI or Gucci Mane or Jeezy (depending on who you ask), but it became what it is today as I became aware of the world around me. And what it is today is a global movement that defined the past decade.

Something that struck me as interesting not too long ago was this trend of trap artists being accompanied by bands and full orchestras. Whether it’s AudioMack’s Trap Symphony series or NPR’s Tiny Desk Concerts, fans can’t get enough of seeing their favorite artists in these settings. This type of content spreads virally because of its juxtaposition. Trap is music based in both street and internet culture and it’s compelling to see it clash with more established, classical forms of music.

Trap feels invincible now, but, as with any musical movement, it will fade and something new will take its place. The distance between these two musical worlds makes me wonder how trap and its legacy will fit into other, more established cultural institutions. When the dust settles on trap’s time at the top, will the genre only be allowed a seat at the table as a novelty act, or will it be given its just due?

To figure this out, let’s look at how the wider umbrella of hip-hop has fared in the race. If we look at the Grammys, the hurdles that must still be overcome are on full display. There’s no need to point out every instance of the Grammys being out of touch when it comes to hip-hop, but it says something that it’s become a yearly tradition for there to be some level of outrage. Neither hip-hop nor trap needs acknowledgment from the Grammys to thrive, but it would be nice to see. It’s a nice thing to see YBN Cordae crying tears of joy after learning he got nominated. It’s a nice thing to see Tyler, The Creator jumping on stage and hugging his mom.

It’s the moments that are still powerful, but then, after they fade away, the system falls back into place and artists are left trying to poke holes in its blatant dysfunction.

Even with as disillusioned as rappers and fans are with the Grammys, they do still matter. Grammys are still used by the general public as a barometer for artistic value, and many iconic acts have fallen victim to the award show bureaucracy and had their careers downplayed as a result. They also matter because representation has to matter. Seeing hip-hop being appropriately honored year-after-year has a ripple effect. Hip-hop Twitter might seem like it’s the whole world, but there are plenty of people who just don’t get the hype. They don’t have to listen if they don’t want to, but seeing it accurately represented gives them a better understanding of its place in society.

A man named A.D. Carson went viral a few years ago after creating a hip-hop album for his PhD dissertation at the University of Clemson. He now serves as an assistant professor of hip-hop for the University of Virginia. In this article written by George Silvarole for the Independent Mail, Carson talks about how Clemson constantly attempted to stymie his project, only to celebrate it as an innovative accomplishment of the university after he defended it successfully. Now in Virginia, he has to deal with this same type of institutional pushback, but in a wider context.

Hip-hop’s integration into academia, even with this constant pushback, is slowly headed in the right direction. There are countless professors today like A.D. Carson who are treating the genre with the respect and validity it deserves. Artists are getting involved, as well. 9th Wonder, Bun B, Q-Tip, GZA and Afrikan Baambata are just a few of the names that have entered the fold themselves as professors. Hip-hop history is valuable in education due to its intrinsic connections to police brutality, city planning, racial identity, and countless other issues that make America what it is today. As Carson’s story shows, hip-hop isn’t allowed to exist peacefully in these spaces yet, but time is slowly chipping away at this. Kendrick Lamar’s Pulitzer Prize win was a massive milestone in this effort and legitimized the art form in certain circles where it wasn’t previously welcome. It also just feels right to me seeing To Pimp a Butterfly and other classic hip-hop albums being immortalized in the Harvard library.

We must celebrate these small victories, but we should still look at them critically. The music that’s being recognized all follows the core tenets of what hip-hop started out as, whether it be the emphasis on lyricism, the types of production, or the connection to wider societal issues. It’s easy to see how the work of a Kendrick can be traced to the fields of both literature and history and be given respect by figures in those disciplines. However, as trap continues to dominate the airwaves, its dominance has to be addressed at some point. These different establishments, after finally accepting hip-hop as artistically valid, will have to look trap music in the face and decide what to do with it. I know that they’ll struggle with it because, for the longest time, I did too.

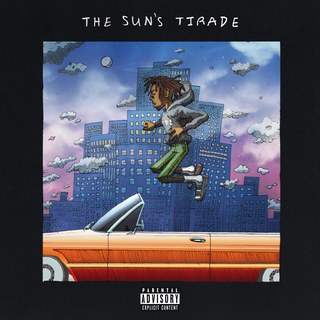

Travis Scott’s Rodeo was my favorite trap album around three years ago, and really the only one I listened to. In Florida, when the night starts running long you notice the humidity more. Maybe because the sun isn’t there to distract you from it. That was when it was time for Rodeo. It felt underworldly and beautiful to me when I drove around back then, like I was some drugged-out spirit lurking through the city.

I loved Rodeo because of its presentation. Travis took trap and elevated it to Broadway levels. He put more effort into capturing an atmosphere than anything else, and the album hit emotional beats that I could relate back to other conceptual albums I loved at the time. However, Rodeo’s cinematic qualities are the exception to trap. Trap music is more concerned with the song than the album. This can be seen in the bloated tracklists, the stories of making 100 songs a day, the lack of smooth transitions between songs, the lack of narrative arcs, the virality of trap singles as opposed to albums, and the high frequency that trap artists put out projects, making each project less of an event and more a dumping of songs.

I used to think of how much more potential trap had if artists would follow Travis’s blueprint: focus on a finite number of tracks, experiment with traditional trap sounds, and put time into sequencing the songs in a way that makes sense. Obviously, I was overgeneralizing a bit, but I still stand by some of this. I also now better understand the causes of some of these qualities while also finding the value in them.

The main reason that trap developed this way is that trap artists were too busy trapping to care about certain things, and who can blame them? When death brushes up next to you every other day, you don’t have time to think about how to best deliver a grand, unique artistic statement. You’re trying to survive.

This raw, unpolished quality is central to trap’s aesthetic. It wouldn’t have the same magic without the low-budget music videos and sometimes same-y production. You can just look at Playboi Carti to see how what could be called laziness can be a positive when paired with charisma and experimentation. Trap’s innovation is focused on the manipulation of voice, not words, which draws a line in the sand between it and most traditional hip-hop. Setting itself aside from more established ways of doing things, it hasn’t died off. It’s thrived as its own entity and become something that’s impossible to ignore.

It’s just everywhere. It’s in pop music, it’s in country music, it’s in R&B, it’s in EDM, it’s in the recesses of Miley Cyrus’s mind as she tries to move on with her life. No one can escape its influence or predict what it’ll look like 10 years from now. If it continues down the path it’s on, it’ll become something almost unrecognizable from where hip-hop started. Even if this is the case, I think there will always be artists whose focus is solely on rapping. From the Grammys and Harvard and historians generations from now, will there only be acknowledgment for this style of rap? If it becomes the minority, would it be inaccurate or unrepresentative if only it got recognition?

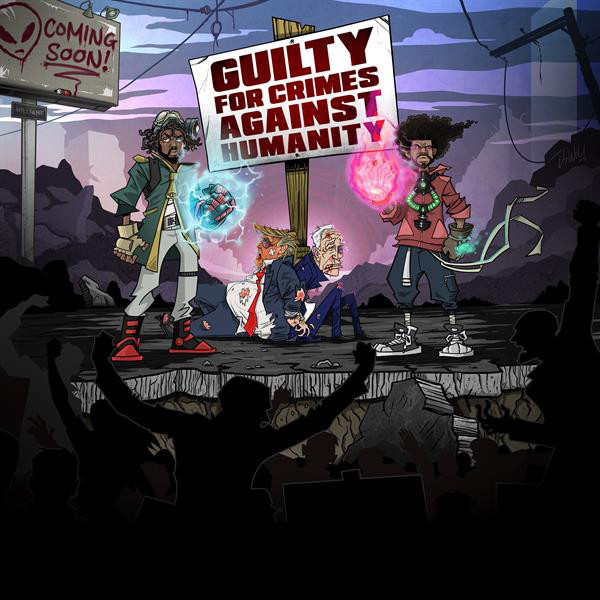

Something else that will hold trap back is its oversaturation. As I mentioned before, most trap artists are desperate to escape their situations and will hop on whatever wave carries them to a place where they can sleep comfortably. This is partly why we have thousands of Migos and Future sound-alikes plugging their Soundclouds day in, day out. In contrast, if we go back to our example of Kendrick, while it’s true that many artists have copied Kendrick’s style, you don’t see them making To Pimp a Butterfly. That album’s unmatched scope and singularity are what make it iconic, but I don’t think that these qualities should be the only ones used in evaluating historical importance. For instance, let’s put To Pimp a Butterfly and Dirty Sprite 2 next to each other. If we consider musical influence alone, TPAB can’t hold a candle to DS2’s accomplishments. I don’t think this can be debated. The response to this is one that makes sense – some variance of “DS2 only has influence because it’s easy for anyone to put autotune on their voice and make something that’s pretty close to what Future made.”

Probably true. However. No one did it like Future did it. No one said “I ain’t got no manners for no sluts/I’ma put my thumb in her butt,” before he did it. No one manipulated their voice like Young Thug until everyone did. No one created a universe of excess and lean that felt more like Houston than if you were actually there until Travis Scott did it. Bottom line, these artists shouldn’t be penalized for what happened after they arrived. They should be celebrated.

It reminds me of this work of art from Craig Damrauer.

How will we look at Future in 50 years? Will he be looked at as a cult hero of our generation?

Will he give lectures at colleges? Will there be an Atlanta trap reunion tour like the Millennium Tour that’s going on right now? Will we all go out on Seniors Night and dislocate our hips to “March Madness?” Will we reminisce over all these toxic memes? How much will his biography sell? Will it be a hot take for him to be called a legend in music, not just hip-hop? These are the things that I think about.

I would never in my life say that Dirty Sprite 2 is better than To Pimp a Butterfly. They’re both great for what they are, it’s just that To Pimp a Butterfly occupies a different, elevated space in my mind. It’s this intangible distance that I’m interested in. I know that it exists in so many of us, and I don’t think it has to. Future is far from my favorite artist, but that’s not the point. Actually, now that I think about it, it may be exactly the point.

This is bigger than preference. It’s bigger than what affects you emotionally. It’s bigger than what gets you through your days. If we want hip-hop to survive, we have to accept versions of it that we don’t necessarily love. As listeners, we rarely get to see the scope of music’s effect. Concerts may be the only time. For so long, we’ve each been in our own intimate relationship with the music, and to be among a mass of people who each have their own intimate relationship with that same material creates a feeling of connection that’s unlike much else.

I am telling you today that this cannot be the only time we band together to celebrate music. We come together now in search of joy, but soon, we’ll have to do so out of responsibility. We grow older every day, and God willing, we’ll make it to a place in life where we have influence over how culture will be shaped. We’ll be the next people running the Grammys, or the next entrepreneurs that create something better than the Grammys. We’ll be the next A.D. Carson, fighting for what we believe in the academic world. We’ll all be in different places, but we’ll be bound by the same thing: holding this era down. It’ll be a minor part of our lives. A sporadic conversation topic. A dismissive comment. A request for your input. In these little moments, we must defend trap as something that was organic and real and defining, and something that deserves respect. Each of us has to get off his or her high horse and ride for the people who shaped the culture of our youth, even if they’re not the closest to our hearts. In a genre predicated on debate and disagreement, are we at least willing to come together for this?

I wonder how Young Thug’s dress looks under museum lights.

Soflosound.com is your one stop shop for a hip hop fan’s music reviews, profiles, and essays. By the youth, for the youth, and allied with all oldheads, everywhere. Leave a comment below on what you want to see next!